From Vietnam to America and Africa, my Peace Corps experience

After graduating from U.C. Berkeley, I joined the Peace Corps and was sent to Togo, Africa as a volunteer to teach high school physics and chemistry.

President John F. Kennedy’s appeal “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country” inspired me since I was still a teenager.

As a Vietnamese refugee, I wanted to give something back to the United States for taking me in, giving me the opportunity to pursue my education and allowing me to live in freedom.

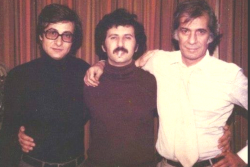

Before leaving the United States, our group gathered in Philadelphia for a week-long pre-departure orientation. There were forty-five volunteers coming from all over the country, most in their twenties and thirties, some sixties. Our discussion concentrated on how to survive and work efficiently in a new environment that was completely isolated and different from where we were living.

The night before leaving, I dined with some new friends in a local Vietnamese restaurant.

We departed on June 16, 1983. Two volunteers, who spoke French fluently, were designated as our guides. The bus was delayed as one person did not show up. A volunteer from Minnesota was still on the phone saying good-bye to his fiance. He told us he would rejoin the group at the airport.

Taking off from Philadelphia, we changed planes in New York and Paris, with stop-overs in Geneva and Adbijan. We landed at Tokoine Airport in Lomé on June 17.

My first impression of this coastal capital of Togo, when seeing motorcycles and pedestrians weaving on streets in an unpredictable manner, was that it looked like the Mexican border town of Tijuana, or Saigon in Vietnam where I was born and raised.

We stayed at Hotel Le Prince located on a dirt road which flooded after the rains. A group of children saw us and shouted in unison “Yovo, yovo. Comment cava bien. Merci.” In Ewe language “yovo” means white people, the first word in a local language we learned.

Togo brought back my fond memories of Vietnam with its hot and humid weather, with papaya trees I saw in a backyard across from the hotel and the red flamboyant flowers still blooming. Those are the things I missed most since my arrival in the United States in 1975.

Togo is a tiny strip of land squeezed in between Ghana and Benin, situated near the equator on the west side of the African coast. Its population is about two and half million people composed of a dozen races, mostly Kabyes and Ewes. Togolese speak different native tongues while French is the official language. Most people follow animism while Christianity and Islam are other religions.

After a few days in Lomé to complete the immigration, work permit and health papers, we were separated by program groups and transported to various locations in the country for training. The first word in French we all learned is “stagiaire.”

The Math-Science training program took place in Atakpamé, a highland town about 160 kilometers north of Lomé.

We spent seven hours daily learning the French language, Togolese cultures and history and pedagogy. Our living quarter was a big room divided into small cubic compartments covered with mosquito nets.

I contracted malaria and was brought back to Lomé for treatment. The Peace Corps doctor wondered why I got it since I was born and grew up in Vietnam. He thought I was supposed to already have immunity from this disease. A dozen of chloroquine pills cured me, but the reaction was terrible. Several friends got diarrhea. Some found learning a new language frustrating. Couple of trainees quit and were sent home as E.T. – early termination.

After the 3-month training course we were officially sworn in as Peace Corps Volunteers.

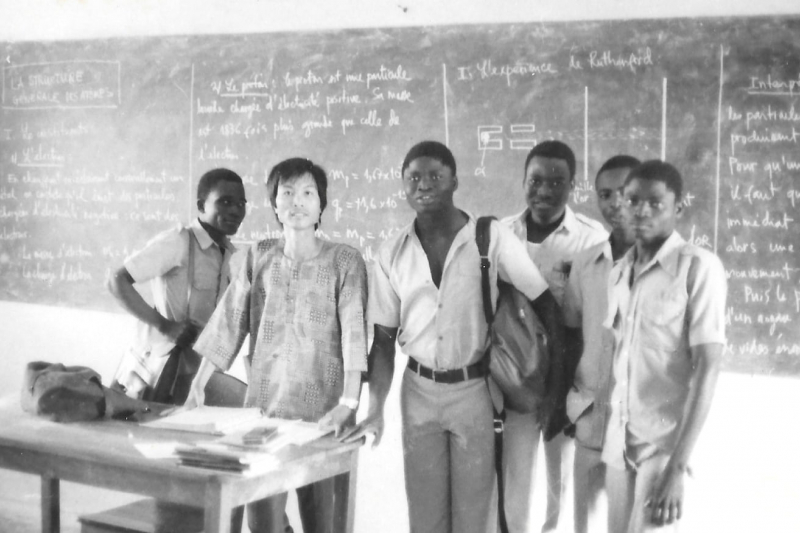

I was assigned to teach science at Lycée de Notsé, 100 kilometers north of Lomé. Two other volunteers, a Michigan State University and a Harvard graduate, got similar assignments father north.

A Massachusetts resident got her assignment to build clay stoves in the northern part of the country. The Minnesota volunteer was posted in the south with an agricultural education assignment.

The couple from Indiana, who previously served in Peace Corps Nepal, were stationed in Lomé to train local English teachers. We became good friends from the day we met and shared a Vietnamese dinner in Philadelphia before leaving the States, we also had a taste of “phở” together at a Vietnamese restaurant in Lomé. A total surprise for me in a new country far away from homeland.

Peace Corps Country Director Bill Piatt took me to my post in a station wagon. I was first presented to the prefecture’s chief, then the principal before arrived at my living quarter.

We unloaded a mattress, two kerosene lamps, a first-aid box, some boxes of teaching materials and my two suitcases. A Mobylette – French moped – and a kerosene mini-refrigerator were placed in the house earlier. The director assured me things would be fine and said good-bye.

I was on my own from now on, in a new land. A little worry but I felt confident. This is what I wanted to do and adjusting to a new life in a strange land was not something new to me. I was resettled in America not long ago and have experienced in learning new language, customs to adapt to a new environment.

My living quarter was a bricked house without running water, electricity or indoor toilet. Mine and several mud houses formed a “concession” – a living quarter, surrounded with corn fields. There was a similar house for a Math volunteer teacher from Ohio who had been here since the previous year.

I began teaching the next day. Lycée de Notsé had some 200 students in six classes. I taught all except one. Ninety percent of my students were males, many in their twenties since students would not be promoted to the next class if they failed the national exam that took place each summer. Less than 50% passing the exam explained why many older students were still in high school.

Teaching physics and chemistry was not a difficult task since I have learned the subjects in Vietnam and again in U.S. university. I spoke French with an accent but my students got used to it. To make my lessons more enjoyable and to illustrate scientific concepts, I brought to the classroom some hand-on activities.

Outside the school I befriended neighbors, who were farmers and carpenters, and learned more about Togolese customs. Listening to music and dancing were their pastime activities. My radio-cassette became their good friend since it broadcast live soccer games, a local favorite sport.

The cemented patio in front of my house was a place for our cultural exchange chats and the sleeping floor for neighbors during hot nights.

The local market met once a week and I could find there tomatoes, carrots and beef to prepare dinner. For lunch I dropped by a local eatery and ordered “fou-fou” and the slimy “sauce de gombo” with chicken, and a bottle of BB beer which were my favorite.

My students gave me an African name “Yaovi” which means a second boy in the family born on Thursday because at school there is already a teacher born on that day.

Togolese did not call me “yovo”, instead they said “Ni hao” when seeing me. No one believed me when I said “Je suis Americain”. In their understanding there are only black and white people in America and I am “un petit Chinois”, not an American.

My neighbors and students often questioned how I could be an American citizen? To their knowledge, Vietnamese were the people who defeated the French, then the Americans, so why did I leave my homeland after the war to follow the loser?

They are excited to hear the story of my escape from Saigon by boat when the communist troops were entering the city and my life in America as a refugee before becoming a U.S. citizen.

I also shared with them the struggle of African and Asian Americans for civil rights and equality in America and told them that Vietnamese were the newest immigrants, with a couple hundred thousand in the United States. Many Togolese considered John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King their heroes. At school, each day I spent several minutes at the end of the period to exchange with students stories about Togo and about the USA.

My neighbors believed foreigners working in Togo had broad knowledge and all kinds of medicines. If someone had a headache, fever or a rash they asked me for some remedy. Some cream or a couple of aspirin tablets were my universal prescription. There was no doctor for several thousand Notsé residents.

My time in Togo was relatively peaceful except for a few scary moments.

After the U.S. Marine compound in Beirut was attacked with bombs, we were advised by embassy personnel on the precautions regarding our safety in the event of anti-American sentiment erupts in the country. The bombing made us worried since we only get world news through shortwave radios.

We also mourned the death of two volunteers. One was killed in a motor accident. The other was our female guide when we boarded the airplane in Philadelphia. She was stabbed in her house by some local people who took revenge for a dispute over her stolen possessions. Her death was an isolated incident but it frightened us all.

I left Lycée de Notsé at the end of the 1984-85 school year. Before leaving I planted some flamboyant trees in the school yard and hoped they would survive the drought so that I could see them blooming with red flowers when I could have a chance to return for a visit.

I remembered the worst drought in 1984 which killed a million people in Africa and the song “We Are the World”. During this terrible famine, I could hear at night the sound from a truck convoy with food aid passing through town on the way to Burkina Faso. Corn fields around my house dried up that year and my neighbors had to consume more yam than corn flour.

Before returning the house key, I gave away all the utensils to my neighbors.

After Togo, I got a job to work with refugees in Southeast Asia and moved there in 1986.

Other friends also continued working overseas. The Indiana couple extended Peace Corps services in Togo for another year before moving to Thailand to work in refugee camps.

The Minnesota volunteer married his fiancé, brought her to Togo, then moved to Mali to work with an AIDS prevention project.

The Peace Corps experience has nurtured our global understanding and culturally enriched our lives. It also made me realize that a happy life does not mean to have everything we need, but rather to have a life full of sharing and learning.

*My Terminale D class, 1984-85 (Photo: Bùi Văn Phú)