PIANO SONATA 14

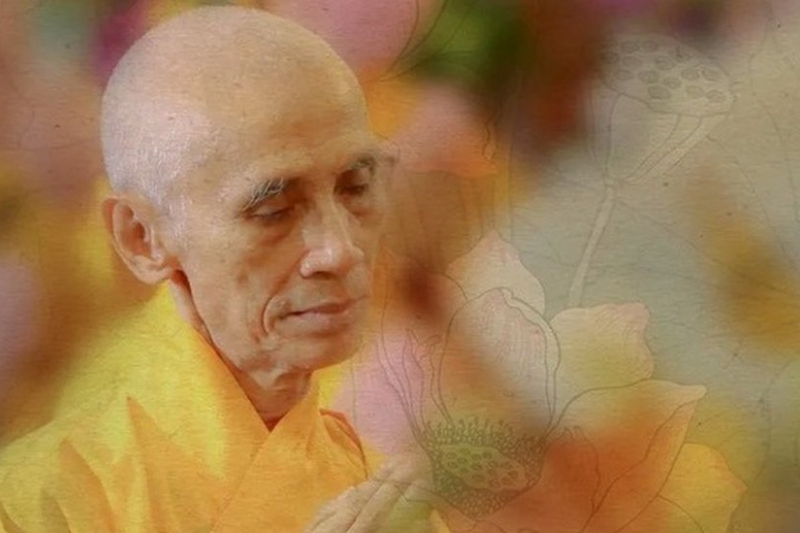

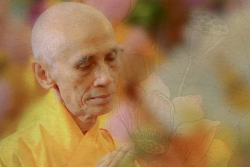

The English translation below is dedicated as my own literary offering to Great Master Tue Sy on the New Year’s Eve.

PIANO SONATA 14

By Tue Sy

Outside the locked gate, a little boy was drawing back against the hedge of hibiscuses. He looked at the quiet monastery in the dark. It was not the first time he came back late; and he, too, was not the only one to come back late. Accidentally or otherwise, the little boys of the monastery had broken a bar of the gate at an end. So, by simply drawing it a little aside, they could slide out and later get back into the monastery easily, of course not forgetting to move the bar back to its former position.

The gate always kept silent since it could not know anything about the boys’ undisciplined actions, nor could the abbot of the monastery. He trusted so firmly in the security of the gate and his predominant presence in the monastery. So he had no doubt that all monastic activities were being regularly carried out under his permanent supervision, and according to strict rules that he always claimed to be absolutely observed. But the boys had sought an exit of their own, and of course none of them would tell him about it. Meanwhile, the gate could speak nothing at all.

It was, however, not by that mutely tolerant gate that Nghi had first slipped out of the monastery. In the back yard was a barbed wire fence, without any hibiscuses or plants of other kinds grown along; and, as a little boy, he found it so easy to crawl out under the lowest wire of the fence onto a nearby vegetable patch, about twenty feet far from which was a small lane, wide enough for two bikes riding side by side.

Then it was by the end of summer vacation.

After the customary practice of evening meditation, Nghi walked to the back of the monastery to take a piss by a thick growth of bananas. Watching the gleaming stream of his urine falling down the grass, he felt greatly comfortable as if his heart were a little enlarged. The rows of fresh vegetables ahead looked nicer than ever. He listened to the rhythm of dancing moonlight as white as mist sparkling on the greens at midnight. The sound was so pleasant and charming. All plants and trees stood still in the peaceful and graceful atmosphere. Listening rather attentively, he could recognize that the sound was coming from beyond the lane. In the monastery it was not rare for the little novices like him to sneak in the shrine to take away bananas from the altars, or slide into the vegetable patch to pick up some vegetable, which would be prepared together with thin girdle-cakes and very hot soy sauce for their secret, interesting parties. So to slide into the patch was nothing unfamiliar to him, though he never took part in sneaking vegetables.

Now the sound from beyond the lane became more and more alluring. Nghi could hardly keep calm. He bent down, crawling under the barbed wires into the vegetable patch. When reaching the lane, he could precisely fix the direction of the sound. At that time not only the lane but even the surroundings were quite deserted. Along the lane there was only a house, hidden behind thick trees. He decided to turn left because it was clear that somebody was playing music over there.

Through the front window of the house Nghi saw a long hair waving gently in harmony with the melodious tunes and slow rhythm of the music. A bit higher was a milk-colored bulb covered in its warm light. Suddenly the music stopped. Nghi was somewhat surprised. He saw a human figure appearing by the window. He wanted to run away but he could not. If he had done so, he thought, he could have been taken to be impolite or even suspected of doing anything wrong. Certainly he would be heavily punished if he was known to have got away from the monastery. Earlier some neighbors had ever complained with the abbot about troubles made by the little novices, and it then was difficult for them to escape punishment.

After a while, seeing that the figure remained unmoved, Nghi was about to run away; but suddenly he heard a female voice from inside the window:

“Who’s there?”

Nghi did not know how to answer when he heard another question:

“You’re a novice from the monastery?”

With such an accent she was undoubtedly a native of Hue. Her voice sounded formal but very gentle. He naturally felt some affection for her.

“Yes,” he said.

“Where are you going when it’s so late?” asked the girl.

Nghi did not answer directly. Instead, he boldly pushed the gate, which was half closed.

“Well, on hearing the music I wanted to see where it was coming from,” he said frankly.

His face appeared clearly in the light from the window. The tuft of his hair dropped ahead, covering part of his front. Under the long, curved lashes were his bright, innocent eyes. Stroking the tuft aside, he said:

“Hi, ma’am.”

“Have you crawled across the fence?” asked the girl.

The little novice smiled, winking his eyes humorously—the smile of a little boy, pure and naive, but so humble and modest in a world fraught with a great variety of formality and solemnity; the scarce childhood of a person who was learning how to hunt for wishes beyond the reach of humanity.

The girl smiled, too. She threw back her long hair and said:

“Come in, Little Novice.”

She walked to the left to open the door, and the boy stepped inside. In the room, besides a small table and a book shelf, there was only one thing strange to him. It was a piano placed close to the wall, opposite the window. He walked there, touching the instrument with his two hands and watching closely the white and black keys arranged in a straight line. His eyes lit up with interest. The girl sat down on a short bench in front of the piano, leaning her upper body against the keyboard.

“Why do you enter the monastery?” she asked.

“I’m living with my Master there,” the boy said.

At this he put his hand on the keyboard and pressed down. Several different notes sounded at once. When he put off his hand, he heard the tones lingering and running into the piano as if they were sinking deep in the vast darkness behind.

“Do you like playing piano?” she asked.

“My Master does not permit it,” the boy said. “Some monks have secretly learned it, but he’ll punish them if he knows.”

“Some monks?” The girl asked in surprise.

“Yes, they’re as old as you.”

“What’s your name?”

“Nghi.”

The boy moved a little aside and stood up, looking closely at the keys. He raised his right fist, then pointed the forefinger at a black key. The finger swept it and touched a white key. One after another the two notes sounded, not regularly.

“Would you like to learn?” the girl said.

“No, my Master would blame me for doing so,” he said, standing on tiptoe to look at the wall behind. The sound might be running back there, he thought; yet, the piano was so close to the wall.

“But you can crawl across the fence as you used to,” the girl said. “It would be hard for your Master to know.”

“I dare not.”

He suddenly turned his back, saying, “I have to go. Bye, ma’am.”

Not waiting for the girl’s reply, he opened the door and ran off. A human figure appeared by the window again, but the boy did not turn back his head.

Crossing the vegetable patch, he crawled through the fence and ran into his room. In the dark a voice suddenly sounded:

“You wretch!”

Then he heard somebody turning over in bed, then a loud slap, and a shout:

“Eh, what’s wrong?”

Nghi knew it was Dam’s voice, and the other was Mui’s, a little novice, because only the latter could often speak in sleep as such.

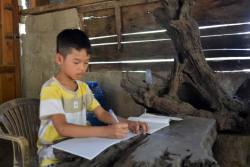

During the days that followed Nghi seemed to forget all about his recent getaway. He was again absorbed in playing with the other boys, in his everyday work in the monastery. His service as a little novice was to make tea, dust chairs and tables, and clean the abbot’s room. No one could know what was being formed in his mind during those days of his childhood. His formality in putting the tea-pot on the tray, his respect in hanging the rosary in the glass-doored cupboard, his deliberation in arranging flowers in the pot, or a pen on the desk, or a book his Master was reading, all of these should not have been the manners expected from those purely black eyes.

Day after day he had to study further the meaning of impermanence, of suffering, of illusions, which were weighing on human life. His eyes remained bright, his smile childish. The human body, made up of four elements, was as impermanent as a tree by the river, a grass on the wall of a well. Were all these things viewed as illusions? Who would dare say that the impermanence and suffering of a human could not be unreal? However, he was fond of learning them, of watching those illusions conveyed in the straight lines of small characters which he always tried his best to copy down as neatly and formally as his Master. Also he was attracted by moon-lit nights. Then, he often walked to the back yard, sitting with his arms clasping his knees in the shade of trees thinking. Among the others of the monastery only the abbot took notice of this, because he knew that the boy then was sitting alone, weeping. Sometimes, seeing him there, he led him back to his room, where he was living with the other three boys nearly of his age.

In a corner of the room was a small altar, made for him by the abbot’s order. Now the other boys were sleeping soundly. The monk lighted a candle. On the altar appeared clearly the half-length portrait of a woman, a little over thirty years old, whose face rather resembled the boy’s. Burning an incense stick and putting it in the incensory, the monk said softly:

“Your mother is still with you. You do not see her, but she does. Don’t weep any more. Your mother would be sad. Sit down with her. Remember to blow out the candle before going to bed.”

Then the monk stepped out.

The boy sat down. He looked at the portrait, then at the flickering candle. He did not know how often he had done so year after year. Every day he was studying hard and playing joyfully with his friends; yet, sometimes, he sat alone, weeping. Thus his body was nightly permeated with the secret warmth from the burning candles in the deeply quiet atmosphere of the solemn, secluded monastery.

Nghi blew out the candle; yet he did not go to bed. He stepped out, lightly closing the door. In the back yard of the monastery the moon was shining. The vegetable patch over there was quiet. He looked at the pile of tiles, which the novices were told to remove there in the afternoon. They would be used, the deacon said, for roofing the Temple of Goddess Five Elements.

In these days there were often intense quarrels among the monks, which were mostly related to the deacon. He was protested by other monks and frequently blamed by the abbot. The deacon assumed that those quarrels might be caused by some conflicts between the elements metal, wood, water, and so on, of the land. So he had the idea that the Goddess Five Elements should be venerated to keep the monastery in peace and security. The temple of the goddess had been built long ago, just before the arrival of the deacon, and even of the abbot. The monastery was once a private temple, which was later donated to the Church as a seat of learning for young monks. As youths, most of them were very mischievous. No sooner had they been received into the monastery than they turned down the incensory on the Goddess’s altar and wrote the four words she has gone off right on the wall where her name-tablet took its place. During the terms of two abbots and four deacons she had not been invoked to occupy her place again until the present deacon had the idea.

Hearing his explanation of why she should be invited to come back, the little novices had a much stronger dislike for her possible return, simply because the monks, if they would be punished for their quarrels, could not have much opportunity to bully them, especially Dam and Mui. Frequently punished by the deacon, these boys wished him to be blamed by the abbot as often as possible. They had suggested Nghi that, after the monks all went to sleep, they would go out together and take a piss on the tiles so that the goddess would give up her idea of returning, if any. They also asked each other not to tell little Dai, whom the deacon liked best, fearing he would reveal everything to him.

Thus, after dinner they had drunk a lot of water so that they would be able to make as much water as possible. The other two boys, however, were then sleeping well while the monks did not yet go to bed. Yet, Nghi, remembering his secret promise, hurried towards the pile of tiles. He completely forgot that he had just wept before the altar of his mother, that the abbot had told him to blow out the candle before going to bed. He climbed up the pile, stood in the middle and, turning himself around, began to urinate just as he were watering vegetable. He felt extremely joyful.

All of a sudden he recalled his crossing the vegetable patch a few days before. Jumping down the pile of tiles, he ran toward the fence, crossing the barbed wires onto the vegetable patch. When reaching the lane, he went on to run into the house of the girl he had seen a few days before but had not known her name. In the light shed through the window, he saw her head hanging over a book, with a pen rolled between her fingers. He held on to the window-sill and climbed up.

“Hi, ma’am,” he said.

Startled, the girl turned back her head. Her eyes opened wide in amazement. How lovely they looked, Nghi said to himself. Not waiting her reply, he said:

“I haven’t got your name.”

The girl smiled. All her appearance, he thought, was different from his mother’s, particularly her smile. He could not remember what his mother’s smile looked like. Nor could he remember if she had ever smiled. The only thing he could know was that in the portrait her mother never smiled. In everyday life, he did not care what some girls’ smiles looked like when they were talking with the monks at the monastery. Yet, on the altar behind the shrine he saw some photos in which the dead smiled. When the novices were told to dust the photos, Dam often spoke loudly:

“Ah, the dead also know how to smile, boys.”

Mui, who then was somewhere about, came up and said:

“Eh, don’t laugh at it. If you do, the retribution will be that your teeth would all fall out.”

Now, in the light from the milk-colored bulb Nghi saw the girl’s smile was so lovely as her eyes.

“My name’s Nhu Khue,” she said. “Is it O.K.? You are so playful, in contrast with your appearance.”

Nghi climbed up the window into the room. He looked disappointed at the sight of the piano already closed. He recalled the sound he had heard that day. The girl could recognize some searching in his eyes, which were slowly sweeping over the instrument. The brown surface of piano was shiny. And his eyes, which were as bright as ever, were sparkling in search of something quite indefinite.

“Would you like to play?”

“Only you can. Not I.”

“Let me teach you,” the girl said. “Your Master would not know.”

The boy hung his head out of the window, watching around. To the right was a small lawn, spreading toward the back of the house. In a corner of the hedge was a sophora japonica. Here and there before him were some clusters of flowers whose names he did not know. The girl walked there. She stood against the window and looked at the garden, too.

“May I teach you how to play piano now?” she said.

“Right now, ma’am?” he was surprised. “How interesting it is! Let me open it.”

Nghi was feeling overjoyed, indeed. He walked back to the piano, watching it carefully, then putting his hands on the iron knobs. Of all the instrument there were only these two knobs that he could get hold of. He drew the knobs and the lid opened up, but he could not pull it out. The upper part of the instrument kept unmoved. Turning it up, he was about to pull strongly when the girl spoke loudly:

“Be careful! It may be damaged.”

She gently pushed the lid into the case of the instrument. Nghi felt very cheerful. His ten fingers swept on the keyboard. The keys competed to move up and down, sounding boisterously.

“It’s too late for you to learn now,” the girl said. “Remember to come early next time.”

“Well, I can’t. I have to recite my lessons to my Master,” said the boy. “Moreover, if I come here so often, he’ll punish me.”

It then was late at night. The suburb was not so far from the center of Saigon but everybody might already go to bed. In the shade of verdant trees the houses, which were thinly scattered, dozens of feet apart, looked much more secluded.

Living in the monastery for a long time, the novice was so much accustomed to everyday visits by numerous pilgrims that he seemed to have given up any discrimination between strangers and acquaintances. To know their faces and names was probably enough for him to regard them as his relatives. So he always showed a very cheerful look, which made the girl feel very close to him. She wanted to give him a kiss on those noble eyes, and at the same time she did not know if the gate of the monastery would be able to detain forever a novice of such graceful poise and bearing. Who could be quite sure to have seen the shadow of worldly illusions in those eyes? She did not know and could not yet know the novice’s respect and his glint which was as mysterious as the smoke of burning sandalwood. Yet, she might, at the present moment, see clearly more than anyone else some intense passion in those eyes, even though she had never felt the intense warmth of a lonely candle, absolutely tranquil at midnight. She suddenly felt, just as a bamboo-painting artist did, that there appeared abundant images of bamboos in her innermost mind. She wished that intense passion would not die out so soon under indifferent monastic rules. Also she felt as if she were gently stroking the little ripples on a lake. Again she sat down at the piano. With her left hand wide open, her thumb and little finger touched two black keys, while the forefinger and ring-finger swept over various black and white keys. Nowhere else could Nghi see such an immense grace as that of her fingers. He stroke his tuft; and suddenly he also opened his left hand and pressed the keys. Nhu Khue shouted, not stopping her playing:

“Don’t be such a spoil-sport!”

Nghi draw back his hand. He turned round to her right. Watching her for a moment, he held out his right hand and pressed down four white keys at once.

“You’re so pesky! I’ll stop playing now.”

The novice stepped back, hiding himself behind her. The girl stood up. She found him bewildered, disappointed.

“How old are you?”

“Twelve.”

“What school do you go to?”

“Ho Ngoc Can. Do you know it?” he said. “I’ve taken morning class there. I’m of the sixth grade next school year.”

“Have you often gone out?”

“You’re asking too much,” the boy said. “My legs are wearing out.”

Taking hold of the window-sill, he jumped up and took a seat there, saying:

“I may not go out without my Master. Otherwise, I have to slip out, like tonight.”

Nhu Khue laughed. This novice was really very much alive. She wanted to touch his tuft and stroke it down along. She stood against the window and looked at the sky. The moon, some stars scattered in the deep night. And how lonely a star in the great distance!

“Are you sleepy?” she asked.

“No,” the novice said. “I often sit up all night on the New Year’s Eve.”

“Why?”

“I’ve been used to,” he said. “Years ago my mother led me to my Master, then she left. In that New Year Festival I couldn’t sleep. I missed her. Some months later my master said she had died. I don’t know where. I have an altar for her in my room.”

Nhu Khue felt his arm touching her. She looked back. He was throwing his tuft aside.

“Do you want to go home now?”

“I will when you feel sleepy. Maybe my Master thinks I were sleeping in my room,” he said. “Ooh! I have to go. Remember to call on my monastery someday.”

He jumped down and ran toward the gate. The girl followed him with her eyes, a white figure dying out quietly beyond the hibiscus hedge.

Walking past the meditation hall, Nghi saw the abbot sitting in a chair, gazing at the front gate. The gate was locked. The road seemed to run without end. The tone of piano sounded freely, lingering into the vast darkness outside. Silently Nghi looked at the back of his Master. He was gazing at the darkness on the road, and he knew it was Piano Sonata 14 played in the style of sostenuto, slow but sinking forever into the dark just as the little waves covered with moonlight were sleeping soundly on the sand.

Soon Nghi, too, knew it was Piano Sonata 14….

~ English translation by Dao Sinh