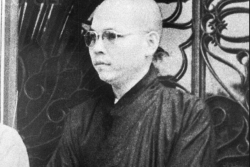

Zen Master Chân Ðạo Chánh Thống

Lê Mạnh Thát: Zen Master Chân Ðạo Chánh Thống (1)

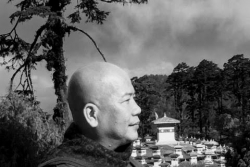

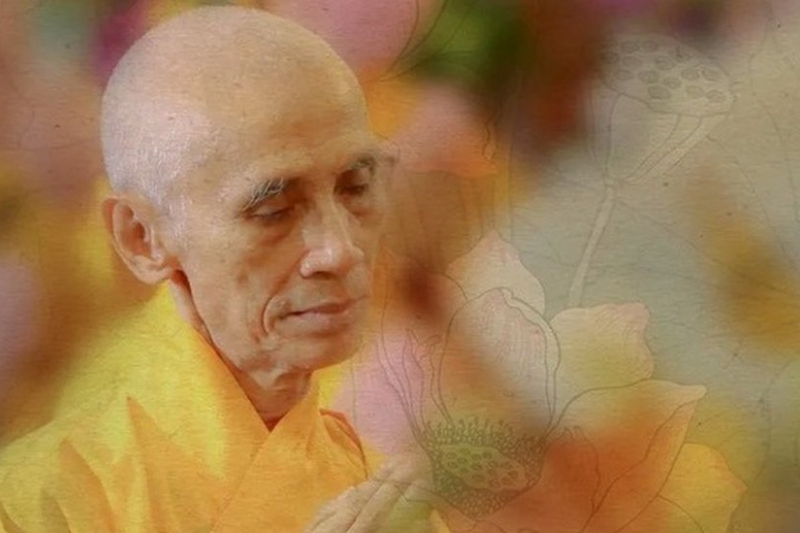

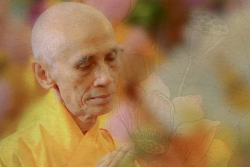

Zen Master Trí Siêu Lê Mạnh Thát (Ảnh: Uyên Nguyên)

The Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao (1) is an anthology by Zen Master Chân Đạo Chánh Thống (2). The Master was born at Trung Kiên village in Triệu Phong district of Quảng Trị province on the 30th of the 12th month of the year Canh Tý, i.e., February 18th, 1901. His father was named Nguyễn Thuyên, his mother Nguyễn Thị Chợ. In his own words his family has piously followed Buddhism for generations and taken Confucianism to be an indispensable factor in a Buddhist’s way of life. The relation between Buddhism and Confucianism was described by him as follows:

I am a native of Trung Kiên in Quảng Trị province. My family follows Zen Buddhism; my grandfather and father possess great knowledge of Confucianism. My family regulations are very strict. Those who fail to observe moral rules are severely blamed. … [My father ever said,] “Fortunately, in the five successive generations of our family Buddhism has been taken as a ‘castle’ and Confucianism as its ‘foundation.’ If you fail to study [how to revive Confucianism] properly, you will hardly escape blames for being a ‘vehicle of gold and silver,’ an ‘old water crane.’ …”

Traditionally, such a view of the interdependent roles of Buddhism and Confucianism may be traced back to Buddhists in Nguyễn Phúc Chu’s time. According to it Buddhists venerated the Buddha but kept their everyday living in the social patterns of Confucianism; that is, “living in Confucianist patterns, aspiring for Buddhist ideals.” Therefore, though he was described as being “often sick and too unhealthy to put on clothes by himself” in his childhood, Zen Master Chân Đạo began his studies at a Confucian school. In 1914 seeing that “the modernist movement was growing strongly whereas Confucian schools were getting deserted,” his father sent him to the Kim Quang Temple in Huế to study Buddhist teachings under Zen Master Ngộ Tánh Phước Huệ (1875-1963) so that he “might not shatter his forefathers’ great expectations.”

In 1919 he was transmitted precepts for Śramaṇera and given dharma-name Chân Đạo, dharma-title Chánh Thống, thus pertaining to the fortieth generation of the Lin-chi lineage in the Thập Tháp Zen sect. Two years later he was officially ordained to be Bhikṣu. After that, he went on to serve his master in Huế, from whom he received a dharma-transmitting gātha together with the further title Bích Phong. Also in this period he began reading The Song of a Warrior’s Wife (3) and wrote two folksongs (4) in the styles of Nam ai and Nam bình respectively in 1924. It may be said that these are among his first works extant in his anthology.

At the age of twenty-five he went to Bình Định to study under Zen Master Phước Huệ (1869-1945) at the Thập Tháp Temple, and returned to Huế in 1929. Thereafter, he joined the movement for reviving Buddhism so that in 1932, when the Annam Buddhist Studies Association was founded, he worked as a lecturer of the Association and was at the same time a “Buddhist college student” of the earliest university course in Buddhist Teachings of the twentieth century run by Zen Master Giác Tiên (1880-1936) and Doctor Tâm Minh Lê Đình Thám (1897-1969) at the Tây Thiên Monastery.

He was known to be a lecturer of the Annam Buddhist Studies Association in around the years 1932-1933; for in 1935 the periodical Viên Âm (5) published his “lecture at the Buddhist Studies Association at the Từ Quang Temple in Huế on the 15th day of the 10th month.” (6) At the beginning of the lecture, which is entitled Tứ Niệm Xứ or The Four Foundations of Mindfulness, he said, “Last year the lecture on ‘The Noble Truth of the Way Leading to Nirvāṇa’ dealt with the thirty-seven prerequisites for the attainment of enlightenment (7); that is, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, the Four Perfect Efforts, the Four Roads to Power, the Five Faculties, the Five Powers, the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, the Eightfold Path.”

In those words it is evident that in 1934 he was invited by the association above to deliver a lecture on the Fourth Noble Truth at the Từ Quang Temple. Accordingly, he must have been in Huế by the beginning of 1934, if not of 1929. The date “1929” is drawn by us from his preface to the two-part version of the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao (8): “In the autumn of the year Kỷ Tỵ (1929) I returned to the imperial capital to found the Buddhist College at the Tây Thiên Temple. The number of students from the four directions became larger and larger.” The character 己, Kỷ in 己巳, Kỷ Tỵ of the version just mentioned is rather faded, so it is easily mistaken for the character 乙, Ất in 乙巳, Ất Tỵ. The latter is, of course, not in accordance with the date of founding the college because it refers either to 1905 or to 1965; so in the three-part version it was replaced with 乙亥, Ất Hợi. Yet, had Ất Hợi (1935) been the year he returned to Huế, he could not have delivered the lecture in the previous year, i.e., 1934, as confirmed by himself in the lecture of 1935. For that reason we are agreed on the year Kỷ Tỵ as recorded in the two-part version.

Otherwise stated, five years after he had received full ordination, he went to the Thập Tháp Temple in Bình Định to study under Zen Master Phước Huệ in 1927. Two years later he returned to Huế, where together with Zen Master Giác Tiên he started some courses in Buddhist teachings, of which was the Advanced Buddhist Course at the Tây Thiên Monastery as recorded in the Preface of his work. This was the preparatory stage for him so that, when the Annam Buddhist Studies Association came into being, he became “the Buddhist College Student” of the first Buddhist University Course run also by Zen Master Giác Tiên at the Tây Thiên Monastery, and at the same time, the official lecturer of the Association, delivering lectures at the Từ Quang Temple in Huế, one of which was published in the Viên Âm in 1935.

Thus, Zen Master Chân Đạo was at the age of thirty-six when he was invited to be lecturer at the Tây Thiên Buddhist College. Also in the words of the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao, in the winter of 1937 when he was thirty-eight years of age, “by Queen-Mother Khôn Nghi’s order the chief patron of the Quy Thiện Temple, His Excellency the Baron Thái (9) with his lady invited me [that is, Master Chân Đạo] to undertake Abbot of that temple and appointed me Tăng Cang (10) with monthly emoluments to lead the abbots and head-monks of other temples.”

As to those positions and emoluments he made a remark, “I would rather remain to be a pine in the cold than enjoy such a little warmth of spring. Then I had a cottage built on the left of the temple, naming it Thủy Nguyệt Hiên, (11) where I could concentrate on studying Buddhist and non-Buddhist literature. Furthermore, my noble and graceful friends, who did not consider my cottage to be a poor, humble place, occasionally visited it during their mountain sightseeing at leisure.”

It was at the Thủy Nguyệt Hiên that many literary and philosophical discussions took place and numerous works were created; hence, the birth of the anthology entitled Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao. Based upon the definitely dated writings in both verse and prose collected in the anthology, a chronological list of Zen Master Chân Đạo’s works may be temporarily made as follows:

– 1924 (Giáp Tý) 中 秋 夜 讀 征 婦 吟, Trung Thu Dạ Độc Chinh Phụ Ngâm, “Reading The Song of a Warrior’s Wife in a Mid-Autumn Night”

– 1934 (Giáp Tuất) 道 諦, Đạo Đế, “The Fourth Noble Truth”

– 1935 (Ất Hợi) 四 念 處, Tứ Niệm Xứ, “The Four Foundations of Mindfulness”

– 1937 (Đinh Sửu) 送 正 信 禪 兄 歸 北, Tống Chánh Tín Thiền Huynh Quy Bắc, “At the Departure of Zen Brother Chánh Tín for the North”

送 素 蓮 禪 兄 歸 北, Tống Tố Liên Thiền Huynh Quy Bắc,“At the Departure of Zen Brother Tố Liên for the North”

– 1938 (Mậu Dần) 智 首 法 契 新 任 波 羅 寺 主, Trí Thủ Pháp Khế Tân Nhậm Ba-La Tự Chủ, “Trí Thủ Undertaking Abbot of the Ba-La Temple”

– 1941 (Tân Tỵ) 中 秋 夜 同 吳 澤 之, Trung Thu Dạ Đồng Ngô Trạch Chi, “Meeting with Ngô Trạch Chi in a Mid-Autumn Night”

– 1946 (Bính Tuất) 訪 敦 后 師 新 任 天 姥, Phỏng Đôn Hậu Sư Tân Nhiệm Thiên Mụ, “A Visit to Master Đôn Hậu on His Undertaking Abbot of the Thiên Mụ”

桃 源 夢 記, Đào Nguyên Mộng Ký, “Record of the Dreams in a Secluded Life”

– 1947 (Đinh Hợi) 次 叔 壄 氏 避 兵 火 韻, Thứ Thúc Giạ Thị Tỵ Binh Hỏa Vận, “A Verse in Reply to Thúc Giạ Thị’s ‘Tỵ Binh Hỏa’”

臘 月 廿 五 寄 覺 本 上 人, Lạp Nguyệt Trấp Ngũ Ký Giác Bổn Thượng Nhân, “Sent to Superior Man Giác Bổn on the Twenty-fifth of the Twelfth Month”

– 1948 (Mậu Tý) 謁 慈 孝 祖 廷 賦, Yết Từ Hiếu Tổ Đình Phú, “A Visit to the Từ Hiếu Patriarchal Temple”

冬 日 詠 梅, Đông Nhật Vịnh Mai, “About a Plum on a Winter Day”

春 日 謁 國 恩 祖 廷, Xuân Nhật Yết Quốc Ân Tổ Đình, “A Visit to the Quốc Ân Patriarchal Temple on a Spring Day”

和 艸 池 先 生 中 秋 韻, Họa Thảo Trì Tiên Sinh Trung Thu Vận, “A Verse in Reply to Mister Thảo Trì’s ‘Trung Thu’”

– 1949 (Kỷ Sửu) 七 夕 疉 去 年 叔 壄 氏 韻, Thất Tịch Điệp Khứ Niên Thúc Giạ Thị Vận, “A Verse Written on the Seventh Night of the Seventh Month in Reply to Thúc Giạ Thị’s Verse of the Previous Year”

初 春 追 悼 覺 本 大 德, Sơ Xuân Truy Điệu Giác Bổn Đại Đức, “In Memory of Bhadanta Giác Bổn Early in the Spring”

– 1951 (Tân Mão) 春 日 訪 圓 通 座 主, Xuân Nhật Phỏng Viên Thông Tọa Chủ, “A Visit to the Abbot of the Viên Thông Temple on a Spring Day”

全 國 佛 教 統 一 大 會, Toàn Quốc Phật Giáo Thống Nhất Đại Hội, “The Great Congress of the National Buddhist Unification”

贈 北 越 素 蓮 法 侶, Tặng Bắc Việt Tố Liên Pháp Lữ, “Dedicated to Dharma-Friend Tố Liên in North Vietnam”

– 1952 (Nhâm Thìn) 留 贈 慧 藏 和 尚, Lưu Tặng Tuệ Tạng Hòa Thượng, “Dedicated to Most Venerable Tuệ Tạng”

– 1953 (Quý Tỵ) 八 月 大 潦 後 賜 薦 難 亡 意 Bát Nguyệt Đại Lạo Hậu Tứ Tiến Nạn Vong Ý, “Offerings to the Victims of the Great Flood in the Eighth Month”

– 1954 (Giáp Ngọ) 承 天 山 門 夏 日 安 居 之 紀, Thừa Thiên Sơn Môn Hạ Nhật An Cư Chi Kỷ, “Record of the Summer-Retreat at Zen Monasteries in Thừa Thiên”

– 1956 (Bính Thân) 智 首 大 師 賜 白 米, Trí Thủ Đại Sư Tứ Bạch Mễ, “Great Master Trí Thủ Giving White Rice”

– 1957 (Đinh Dậu) 秋 月 慈 恩 寺 晚 眺, Thu Nguyệt Từ Ân Tự Vãn Thiếu, “Watching the Từ Ân Temple in an Autumn Evening”

下 山 觀 展 覽, Hạ Sơn Quan Triển Lãm, “Leaving the Temple for an Exhibition”

– 1958 (Mậu Tuất) 十 塔 寺 開 講 日 訓 示, Thập Tháp Tự Khai Giảng Nhật Huấn Thị, “Instructions on the First Day of the School Year at the Thập Tháp Temple”

– 1959 (Kỷ Hợi) 中 秋 月 夜 六 十 自 詠, Trung Thu Nguyệt Dạ Lục Thập Tự Vịnh, “A Poem Written on Myself at the Age of Sixty in a Mid-Autumn Night”

釋 尊 寶 誕 恭 紀, Thích Tôn Bảo Đản Cung Kỷ, “In Respectful Memory of the Sacred Anniversary of Śākyamuni’s Birthday”

贈 明 齋 陳 君, Tặng Minh Trai Trần Quân, “Dedicated to Sir Minh Trai Trần”

– 1960 (Canh Tý) 自 恣 日 恭 紀, Tự Tứ Nhật Cung Kỷ, “In Respectful Memory of the End of a Summer-Retreat”

– 1962 (Nhâm Dần) 釋 尊 誕 日 恭 紀, Thích Tôn Đản Nhật Cung Kỷ, “In Respectful Memory of the Sacred Anniversary of Śākyamuni’s Birthday”

– 1963 (Tân Mão) 釋 尊 誕 頌, Thích Tôn Đản Tụng, “A Gātha on Śākyamuni’s Birthday”

弔 逍 遙 禪 師, Điếu Tiêu Diêu Thiền Sư, lit. “Attending Zen Master Tiêu Diêu’s Funeral”

While he was teaching at the Tây Thiên Buddhist College, he received a visit paid by Zen Master Tố Liên from the North in 1937. No doubt, these two masters discussed the unification of Buddhism after the three major parts – North, Central, and South – of the country had founded their own Buddhist Studies Associations; and they also severely criticized the view that some discussion about Buddhist unification might be pure nonsense, as mentioned in the last two lines of a seven-character regulated verse by Zen Master Tố Liên, which was later cited by Zen Master Chân Đạo in his anthology,

法 軌 將 來 君 得 志

三 圻 合 徹 妄 談 耶

How satisfied you are with the view of Buddha-dharma in the future!

That the three parts may be totally unified is hardly nonsense.

Also in this period he went on to teach at the Từ Quang Temple of the Buddhist Studies Association. The temple was then under the charge of Zen Master Giác Bổn, whom he had very close relations with and dedicated several poems to in his anthology. From 1937 on it was evident that he might go to the North, where he met with Zen Master Trung Thứ so that he could write a poem in reply to this renowned Zen master’s.

In 1941 at the invitation of District Chief Ngô Đình Nhuận he attended a musical performance. At that time the World War II broke out, and the movement to struggle for freedom and independence of our country was going on strongly. With regard to this gloomy circumstance Zen Master Chân Đạo expressed his feeling in the following lines:

相 將 握 手 上 江 樓

聽 曲 無 端 為 氐 愁

清 似 啼 鵑 懷 故 國

細 如 嫠 婦 泣 孤 舟

Walking up the river pavilion hand in hand together,

I spontaneously felt deeply sorrowful at the melody,

Which sounded clearly like the cry of a homesick bird,

And softly like a widow’s weeping in a lonely boat.

In the years that followed 1941 he might write some poems to present his view and emotions about contemporary political events; yet, probably on account of their political content they were not written down in his anthology. Not until 1946, when Zen Master Đôn Hậu began undertaking Abbot of the Linh Mụ Temple, he wrote a poem to record his visit to him.

Having been evacuated from Huế, he returned in 1948 and visited some temples, of which only the Quốc Ân Patriarchal Temple and the Từ Hiếu Patriarchal Temple were mentioned in the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao. In 1949 at the passing away of Zen Master Giác Bổn he wrote a poem in memory of him; and in a great ordination organized at the Báo Quốc Temple for the purpose of stabilizing the Buddhist Order he, in his service as a secretary, composed a writing in the style of phú to celebrate this great event.

In 1951 a great congress was held to discuss the unification of the individual Buddhist Studies Associations across the country, of which the result was the birth of the General Association of Vietnam Buddhism. Zen Master Chân Đạo had participated in and written poems to congratulate the congress on its success. A year later during a congress held in the North to discuss the unification of the Buddhist Monastic Order, he wrote a poem to congratulate Zen Master Tuệ Tạng on his appointment as Head of the Saṃgha. After that he went on with his teaching. In 1958 he was invited to the Thập Tháp Temple in Bình Định to teach at a course in Buddhist teachings, whose students were, later, Zen Master Khế Châu, Zen Master Mật Hạnh, and so on.

On the 22nd of the 12th month of Đinh Mùi, i.e., January 21st, 1968 he passed away. His śarīra was enshrined in a stūpa just in the grounds of the Quy Thiện Temple. A student of his wrote a ‘couplet in parallelism’:

Thầy đã đi rồi, bể Thích rừng Nho trông vắng vẻ;

Con còn ở lại, kẻ tăng người tục thấy bơ vơ.

You have passed away, Master. How deserted the Buddhist ocean and the Confucian forest appear!

Your students, both monks and laymen, are gathering here. How desolate we feel!

And another one by Zen Master Tâm Như Đạo Giám Trí Thủ is cited below as a conclusion of our writing about Zen Master Chân Đạo’s life – a life that was totally devoted to the cause of education and literature for both Buddhism and nation.

昔 年 法 乳 同 沾 誓海 者 曾 盟 鐵 石

今 日 曇 花 先 落 禪 林 誰 是 耐 風 霜

Of old we drank Dharma-milk together, arousing firm resolutions in the ocean of vow.

At your passing away as the first fallen udumbara (12) flower, who in the Zen forest is now able to suffer ‘fog and wind’?

~ English Translation by Dao Sinh

———————–

Notes:

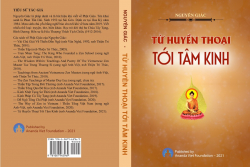

(1) 水 月 叢 抄, lit. The Copying of the Anthology [by the Owner of] the Thủy Nguyệt Cottage

(2) For short, Zen Master Chân Đạo.

(3) Chinh Phụ Ngâm Khúc

Romanized Vietnamese is employed in the present translation to transliterate all that is originally written in Chinese or Quốc Âm.

(4) Hò Mái Nhì

(5) No. 18, pp. 26-39

(6) i.e., November 10th, 1935

(7) Skt. bodhipākṣika-dharma

(8) His anthology is preserved in two different editions; one is composed of two parts, the other of three parts.

(9) Full title: Đông các Đại học sỹ Nam tước Thái Tướng công

(10) Rector of a community of Buddhist monks

(11) 水 月 軒, lit. the Cottage [named] ‘the Moon [reflected in] the Water’

(12) Skt.; a tree that is said to blossom only once every three thousand years. Therefore, it is often used as an illustration of how hard it is to come in contact with Buddhist teachings as well as to be born in the time of a Buddha.

Lê Mạnh Thát: Zen Master Chân Ðạo Chánh Thống (2)

Zen Master Trí Siêu Lê Mạnh Thát (Ảnh: Uyên Nguyên)

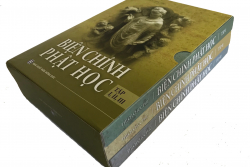

WORKS OF ZEN MASTER CHÂN ĐẠO

Composed of more than 400 writings in verse and prose the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao is an extremely copious anthology, whose content is expressed in various literary genres. As for prose different styles such as ‘biền ngẫu,’ ‘phú,’ ‘ký,’ ‘chí,’ etc., are used. As for verse the author calls into play all the styles found in Chinese poetry such as ‘couplet in parallelism,’ eight-line regulated verse with five characters to a line, eight-line regulated verse with seven characters to a line, four-line truncated verse with five characters to a line, four-line truncated verse with seven characters to a line, and ancient style. Besides, a style typical of Vietnamese poetry called song thất lục bát (13) is used by the author for writing poems in Chinese. It may be said that they are the only “song thất lục bát” poems written in Chinese script of Vietnamese literature.

Some literary critics in the world have usually analyzed and studied literary works in terms of literary genres employed by their authors. This method of literary criticism proceeds from a regular phenomenon that a certain phase of literature is often characterized by a definite literary genre, which is in its turn to regulate the content of the same literary phase. In China, for instance, literary phases are often dealt with according to their own guiding literary genres such as 賦 during the Han Dynasty, 詩 during the T’ang Dynasty, 詞 during the Sung Dynasty, 劇 during the Yüan Dynasty, 小説 during the Ming Dynasty, and so on. The method has sometimes been applied in Vietnam, chiefly for literature during the Lý and the Trần Dynasty, in which the number of literary works is not large.

Apart from some advantages just mentioned the method has, however, some fundamental defects, one of which is its failure to present a panorama of literature of a definite phase or of an author, particularly of classical authors or those of classical type like Zen Master Chân Đạo. For them literature is regarded as a means to convey their views, or rather, their reflections on themselves and the age in which they find themselves. Zen Master Chân Đạo himself also declares his similar view in the Preface to the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao: “verse is for exposing one’s aspiration, prose is for expressing one’s feeling. Therefore, those who were interested in the public life wrote verse as Tu Fu, 杜甫; and those who made use of things to represent their personal emotions were mostly of the same type as Ch’ü Yüan, 屈原.”

The view of “verse for exposing one’s aspiration, prose for expressing one’s feeling” was obviously advanced in Chinese literature in the old days, at least in Confucius’s time; for it was in the Preface to The Book of Odes, 詩 經, that Confucius formulated it. Thus, in classical literature verse and prose were conceived to be a way of exposing aspiration and communicating feeling, which was later summed up in the expression “Literature is for conveying the Tao.”

It is from such a literary view that we understand why and how the contents of Zen Master Chân o’s anthology were arranged in its present form. Indeed, the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao was not based upon any definite genre of literature; that is to say, his writings whether in verse or prose are not arranged in accordance with the genres in which they are created. Consequently, it may occur that a poem is sometimes found to be followed by a writing or vice versa, and sometimes a five-character regulated verse is followed by a five-character truncated one, and so forth.

POETRY – A MEANS OF CONVEYING ASPIRATION

No doubt, such an arrangement, though it might make an impression of some disorder in the whole anthology, does represent the author’s view of “verse for exposing aspiration, prose for expressing feeling.” Indeed, both copies of the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao begin with the text called Repentance (14). The date when it was written is not known. Yet, as a text of repentance it may rather fully represent the afore-said view of literature and art; that is, the author’s aspiration for serving sentient beings in the Triple World (15) with all his heart. In Vietnam it is the aspiration that Buddhist practitioners in all monasteries have to arouse within themselves every day. It is originally conveyed in a phrase extracted from a sūtra that has been recited at morning service in Buddhist temples and monasteries in Vietnam for centuries. So, if that is the aspiration Buddhist monks have to raise in their mind very early in the morning, what must they do to realize it? Let us read the next phrases, “we vow to be the first to enter the evil world of five impurities [for the benefit of all beings],” (16) and “we refuse to enter Nirvāṇa until the last being [in the Triple World] gets perfectly awakened.” (17) Obviously, the aspiration for engaging oneself in the “evil worlds of five impurities,” that is, in the realms fraught with hardship and suffering, has been put forward to be the top mission of all Buddhist followers in monasteries as well as amidst the world. In his own words we have known that Zen Master Chân Đạo was born of a Buddhist family. The date he came into existence, too, was the time when French Colonialists had just finished their campaign of occupying our country by force and began to carry out their extremely savage policy of colonial exploitation (1897).

A chain of events took place, some of which were the elimination of our traditional education in Chinese script and the introduction of Quốc Ngữ or Romanized Vietnamese as the official script of the country. These events engendered the movement to copy the so-called new culture, which was boosted by French Colonialists in their plot to enslave the Vietnamese for long, as in the words of a Christian priest who, then, was working in the North of our country: “The matter is of great importance. And subsequent to the founding of Catholicism, I think, the abandonment of Chinese script and the step-by-step substitution of Annamese [that is, Romanized Vietnamese] for it, and then the whole substitution of French are a measure, very political, very convenient, and very effective to found in the North a little France of the Far East.” (18)

To abandon traditional education was aimed at eliminating the intellectual circle in Vietnam, that is, all the intellectuals of the day. As far as its reason was concerned, it was Puginier who had said to Governor-general De Lanessan in 1887, “Because the intellectuals have a very great influence, very great prestige, and are respected when they serve as officials, it is necessary to eliminate them. As long as they exist, we will have to fear everything. For with their warm patriotism they refuse to recognize our domination; moreover, none of them agree to follow Catholicism.” (19)

This is the very germ of the situation described in Zen Master Chân Đạo’s words as “the modernist movement was growing strongly whereas Confucian schools were getting deserted.” In that period Confucianism had organic relations with Buddhism, as the Master’s father stated, “Fortunately, in the five successive generations of our family Buddhism has been taken as a castle, and Confucianism as its foundation.” The view of an organic connection between Buddhism and Confucianism was a great policy of Buddhism in the age of Nguyễn Phúc Chu (1692-1715), when the view of “living in Confucian patterns, aspiring for Buddhist ideals” began to affect all the subsequent developments in the history of Vietnamese Buddhism.

Yet, by the time Zen Master Chân Đạo was born, Confucianism no longer remained positive, and it was being overpowered by the enslaving cultural movement mentioned above. Those Buddhists who held the view of “living in Confucian patterns, aspiring for Buddhist ideals” as his father inevitably felt highly anxious and could not fail to urge their subsequent generation to seek to revive the Confucian role in social life after they had analyzed the course of its formation in the history as well as its present state:

If you fail to study [how to revive Confucianism] properly, you will hardly escape blames for being “a vehicle of gold and silver,” “an old water crane.” Those who have concerned themselves with Confucianism would find it hard to remain silent at the tragic fact that its true face, which was first covered in the ages of Hsin and Han and then by debased Confucianists on a larger scale, is being much more distorted by false statements from the supporters of the Modernist Movement. Moreover, the throng of scholars who are secretly misusing the doctrine of “dependence upon the circumstances” is not of small number. Reflecting upon our forefathers’ favor of nurturing and educating us, we feel extreme shame at not being able to repay them so much for their favors as those birds for their mothers’.

While reviewing the course of Confucian development in the history, Zen Master Chân Đạo’s father paid attention to the degeneration of this doctrine just in his age when a number of Confucianists made use of the principle of “dependence upon the circumstances” to plead for their pursuit of the modernist movement, of which he himself never showed approval. As a consequence, the most urgent requirement for Buddhists at the time was that they had to retreat into the Buddhist “castle” as a final support whereas the Confucianist “foundation” was being violently attacked. This explains partly why the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao, which came into being in a period when “Confucianist education is already obsolete” as in Trần Tế Xương’s remark, was composed in Chinese.

After they had retreated into the Buddhist castle, the immediate demand for them was to “forsake trivial phrases and penetrate marvelous implications so that the ‘sun’ of meaning could shine more and more brightly, the ‘ocean’ of enlightenment could become as pure as possible; hence, not disappointing their forefathers.” In spite of this, Buddhism in Vietnam could not show a shadow of hope in the gloomy situation of the whole country. Following the uprising of Đoàn Trưng Nguyễn Văn Quý, which was suppressed in bloodshed in 1868, and particularly subsequent to the uprising of Võ Trứ in Phú Yên with the assistance of Trần Cao Vân in 1896, the life in Buddhist monasteries which had been reduced to the minimum became more and more declined in a country without sovereignty.

When Zen Master Chân Đạo began his monastic life under the instruction of Zen Master Ngộ Tánh Phước Huệ at the Kim Quang Temple in Huế in 1914, “the daily routine in monasteries was worse than any harsh policy, in which interest was shown not in education but in raising livestock. Laughing and crying on the occasions of welcoming and seeing off respectively were regarded to be unwholesome. Life in monasteries was unstable. Not much of the knowledge of Buddhist teachings was acquired. The more I expected, the more disappointed I felt,” as in the Master’s words.

Such was Buddhist education in the first decades of the twentieth century that it required a fundamental change, which was later commonly called the Buddhist Revival Movement and in which Zen Master Chân Đạo enthusiastically participated from the very beginning. A few years after being ordained to be a Buddhist monk, he went to the Thập Tháp Temple in Bình Định in 1928 and studied under Most Venerable Phước Huệ (1869-1945), as recorded in a note to the poem “Falling Ill in the Western Pavilion of the Thập Tháp Temple” (20) composed in 1958, “I recall I fell ill while I was studying there thirty years before.”

Though it was said that “interest was shown not in education but in raising livestock” during the first decades of the twentieth century, there were actually some seats of learning for the succeeding Buddhist generation. In the North there was the Vĩnh Nghiêm Patriarchal Temple under the charge of Patriarch Thanh Hanh (1840-1936) in Bắc Giang. In the Central was the Báo Quốc Patriarchal Temple presided by Patriarch Hải Thuận Diệu Giác (1801-1891). Of his nine disciples whose dharma-names all began with the word Tâm was Patriarch Tâm Tịnh (1879-1929), founder of the Tây Thiên Temple where the first Buddhist college of the country was built in 1935. In the Preface to the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao it is recorded that Zen Master Chân Đạo took part in founding this college and teaching there, “In the autumn of Ất Hợi (1935) I returned to the imperial capital to found the Buddhist college at the Tây Thiên Temple. The number of students from the four directions became larger and larger. Besides Buddhist teachings, Confucianist literature, which was rather useful to students, was included.” In the South there was the Giác Lâm Patriarchal Temple founded by Patriarch Hoằng Ân Minh Khiêm (1850-1914), where many prominent monks and writers of the South such as Patriarch Từ Phong (1864-1938), translator of the 歸 源 直 指 演 義 , (21) were educated.

In addition to those big centers of learning, there were dozens of smaller ones which, due to the war against French colonialists, were organized on a small scale but could also produce outstanding Buddhist figures in the first half of the twentieth century such as Most Venerable Trung Thứ (1871-1947), Zen Master Tố Liên (1903-1977) in the North, Zen Master Viên Thành (1874-1929) in the Central, Zen Master Khánh Hòa (1877-1947) in the South, and so on.

Thus Buddhist education in the first decades of the twentieth century had remarkable achievements. Not only did it produce a highly competent force for Buddhism but it also devoted talented citizens to the country in the long struggle for national independence. In spite of this, our country at that time did not yet restore sovereignty and cultural tradition, let alone Buddhism which was then being violently persecuted. Consequently, the aspiration for “serving the world with all one’s heart,” which Zen Master Chân Đạo referred to, really reflected the general attitude of a Buddhist generation towards the existence of nation as well as the fate of Buddhism at the time.

Naturally, the fact that Zen Master Chân Đạo, as being a Buddhist, vowed to serve with all his heart sentient beings in the world implies first his faithful service to Buddhism, which has been publicly determined since Zen Master Định Không’s time (730-808) to be the abiding principle of Vietnamese Buddhism: Buddhism incorporated in national existence. Accordingly, to serve Buddhism is, in Vietnam, a way of serving the nation. Commonly, in order to serve something it is necessary to understand its true needs as well as its circumstances. If so, what are true needs and circumstances of Buddhism in Vietnam at Zen Master Chân Đạo’s time?

Its circumstances have been partly pointed out in his description that “the daily routine in monasteries was worse than any harsh policy, in which interest was shown not in education but in raising livestock.” For that reason, the primary need was to improve Buddhist education by transforming individual educational institutions in monasteries and Buddhist centers mentioned above into large-scale educational institutions, in which both monkhood and lay people would have equal opportunities for studying Buddhist teachings and applying them to their everyday living so that they could no longer carry on any improper activities due to their lack of knowledge.

We have seen that just as the Tây Thiên Buddhist College was founded, Zen Master Chân Đạo as being a student of it could deliver a lecture on the Fourth Noble Truth at the Từ Quang Temple in 1934, and another one on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness a year later. The former was not published, but the latter was inserted in the Forum of the periodical Viên Âm in 1935. It is his only extant lecture written in Vietnamese and one of the first writings in Vietnamese prose of Buddhist literature in the twentieth century. This points out the indispensable need of expounding Buddhist teachings to Buddhist followers at the time.

Later on he was still interested in education until his death. In 1958 when a Buddhist college was founded at the Thập Tháp Monastery, where he had ever taken Buddhist courses as a young monk, he was invited to work there as a lecturer in Buddhist Teachings. In his Instructions at the opening ceremony of the new school year his aspiration for serving the cause of Buddhism was once again raised. He stressed the fact that Buddhism in Vietnam was then being persecuted by the regime of Ngô Đình Diệm, and that his students should bravely defend against it: “A Great Man whose aspiration is nurtured as lofty as Heaven should not aim at where the Tathāgata passed. It is, however, a pity that the evil is much stronger than the good such that those possessing wide knowledge and profound understanding all feel anxious. Let’s ‘go straight to the dragon’s den to take the pearl from inside its jaws’ instead of remaining inactive in our thatched cottage, and bravely do righteousness just on the very site of recreation. Only if one can do so is one then to be called a Great Free Man with unlimited capacity.”

Those enthusiastic instructions naturally had their own effects. They were delivered to a generation of young monks, of whom some would become pivotal figures of Buddhism in Bình Định a few years later. Accordingly, it may be said that his instructions could raise some consciousness in Buddhist monks of their responsibility for the growth of Buddhism. In this connection, it would not be an exaggeration for us to say that those instructions actually made a remarkable contribution to the achievement of the 1963 Buddhist Movement just in its preparatory phase.

Those educational activities, which Master Chân Đạo determined to be of his major task, were tenaciously carried out for a long time, at least until the 1962s, when we were taking the last course in Buddhist teachings at the Quy Thiện Temple, of which he took charge for nearly thirty years. It was his enduring efforts in the field of education that helped improve the knowledge of monastic Buddhists and eradicate those evils which ever caused some misunderstanding of the Buddhist role in society. One of these evils was that Buddhist monks’ activities began to show the increasingly general tendency towards gratifying lay Buddhists’ ritual needs rather than instructing them to apply Buddhist teachings to their everyday living.

In reality, as the Annam Buddhist Studies Association was founded, the first task it set forth consisted in two main points, as recorded in the Viên Âm No. 14 (1935); that is, (1) improving way of life in the Buddhist Order with the emphasis laid on monastic rules by means of close supervision of Brahmācāra or Pure Conducts of the monkhood; (2) restricting conducts harmful to the reputation of Buddhism, of which the trend towards meeting lay Buddhists’ needs for religious rituals had to be noticed and changed. In the Thủy Nguyệt Tòng Sao it is evidently shown through a series of his works that Master Chân Đạo participated positively in the carrying out of this task.

“A Judgment in Behalf of the Buddhist Association in Thừa Thiên Province,” (22) for instance, tells us about the case of a monastic member who “possessed neither a trace of ink in his bosom nor an easiest-to-write character in his eyes” and had such “unwholesome livelihood” that he should be purged from the Order. Here by “unwholesome livelihood” it undoubtedly refers to some way of making living not in accordance with Buddhist disciplinary rules. In addition to this, it was necessary to reorganize Buddhist activities systematically, particularly in monasteries, by holding traditional ordinations for the purpose of “guiding the subsequent generation and preserving the Buddha-wisdom,” in which Master Chân Đạo was greatly interested and took part warmly as recorded in his writings such as “The Ordination Schedule.” (23)

Furthermore, it was necessary to criticize disputes among some members of the Buddhist Order, which would weaken the practice of Buddha-Dharma and turn the sacred temple into the “land of dense undergrowth,” “the place of unpleasant troubles,” and cause the growth of unwholesome ideas. In the words of “Competition between Certain Monks for the Head of Temple,” (24)

晨 昏 攝 念 禮 空 王

世 事 徒 勞 莫 較 量

憎 愛 未 忘 知 法 弱

怨 親 難 解 恨 魔 強

祇 園 化 作 荊 楱 地

淨 境 翻 成 熱 惱 場

警 醒 愛 河 名 利 客

却 酣 利 鎖 與 名 繮

Pay homage to King Śūnyatā (25) attentively morning and evening

Instead of concerning yourselves with troublesome affairs in the world.

Hatred and desire being not destroyed, the practice of Dharma would be weakened;

Enmity and friendship being not abandoned, the force of Passions would be strengthened.

The Jeta Park (26) has become the land of dense undergrowth;

The Pure Land has turned into the realm of unpleasant defilements.

I advise those who are still attached to passion, fame and interest

Not to be infatuated with the “lock” of interest and the “rein” of fame.

Those disputes were chiefly caused by some monks’ pursuit of fame and interest. From his view not only lay people were occupied with striving for fame and interest, but a number of Buddhist devotees who had been practicing the control of their minds showed their desires for humble values of the world. In the words of “Fame Persuading Interest,” (27)

君 不 見

釋 徒 守 高 潔

避 我 畏 君 似 蛇 蠍

遑 知 內 外 不 相 關

心 慕 吾 儕 如 聖 哲

You have not seen

That Buddhist followers who are leading pure and noble lives

Keep away from you and me as from snakes and centipedes.

Only those unaware of the relation between the inward and the outward

Respectfully regard us to be saints and sages.

On the other hand, it was necessary to appreciate the preservation o